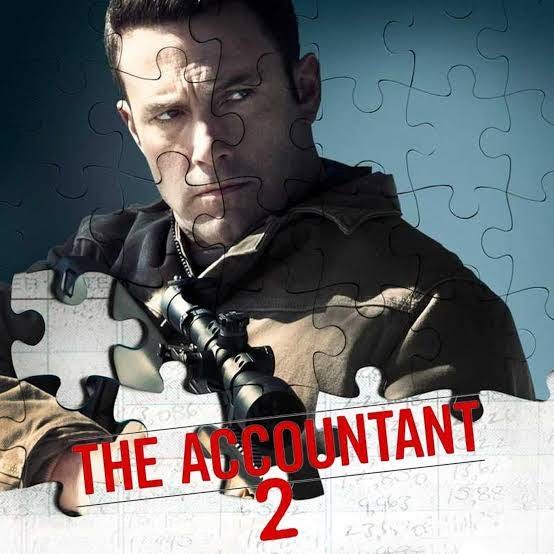

I just saw The Accountant 2, and once again I’m struck by Hollywood’s obsession with the emotionally guarded, hyper-competent man who kills with precision and solves equations with equal ease. This trope—part savant, part assassin—shows up again and again. From Jason Bourne to John Wick to whoever Ben Affleck’s Chris Wolff is supposed to be, we clearly love a man who weaponizes intellect and trauma in equal measure. And more importantly, we accept that his pain justifies his violence. The logic goes: if he’s been through enough, then the body count makes sense. We don’t just tolerate it—we root for it.

Chris is a fascinating kind of hero. The film doesn’t really ask us to question the violence—his skill set is part of the fantasy—but his real arc is emotional. He’s learning to connect. To trust. To relate to others without needing a tactical reason. And the most touching relationship in the movie? The one with his brother Braxton (Jon Bernthal). Their bond is real, but their love language is violence. They’re most in sync when fighting side-by-side, their connection forged in bloodshed and survival.

But what struck me even more were the characters who helped him along the way—other neurodivergent people, specifically autistic characters, who were often overlooked or underestimated. These characters are efficient, focused, and crucial to solving cases—more so than the "professionals" they assist. They’re not sidekicks, and they’re not there for show—they’re better at what they do than anyone else, but their value is largely ignored by the systems around them.

Is this the film’s subtle commentary on disability? By showcasing these characters as hidden assets, the film seems to suggest that neurodivergent individuals can be not just competent, but superior—yet society continues to overlook them until they’re needed. It’s a quiet message: when difference is only acknowledged for its utility, is it just another form of exploitation?

There’s something sad and telling about all of this. Chris can calculate risk in nanoseconds, take out an entire room, and file taxes for the mob—but emotionally? He’s learning in baby steps. And that’s what the movie asks us to cheer for.

Which makes me wonder: what does it say about us—as a culture—that we keep coming back to this version of masculinity? One where trauma isn’t healed, just redirected into combat? Where connection happens through shared wounds, not vulnerability? And where neurodivergent people are only seen when they’re useful, not when they’re human?

The Accountant 2 may be solving equations, but we’ve still got a lot of questions.

You are on point as usual and raise good questions. I feel like having the neurodivergent individuals shown as superior and not competent, or worse, is a silver lining. And there's always a sense of satisfaction when justice prevails, whether through vigilante means or not.